DeVillers brought in to investigate Tri-Valley

August 8, 2022

The former U.S. Federal Prosecutor for the Southern District of Ohio, David DeVillers, and an associate at his firm Barnes & Thornburg were tasked with investigating employees at Tri-Valley Local Schools, an investigation by Y-City News has discovered.

In a deviation from typical practice, Muskingum County Prosecutor Ron Welch selected the two private practice attorneys to investigate district staff members connected to the criminal case of Cory Marling, the former principal who sexually assaulted multiple elementary-aged children, initially indicted on 11 felony charges, before securing a plea deal that allowed him to avoid prison and being required to register as a sex offender. Marling will be released later this year after only serving 340 days in the county jail.

Unlike in dozens of neighboring counties, Welch chose not to select special prosecutors from a nearby county or from the Ohio Attorney General’s Special Prosecutions Division, but from the law firm which charged nearly $400 an hour for their services.

DeVillers hadn’t at that point prosecuted a state case in decades, but had recently done quasigovernmental investigations, such as those into state colleges, at the request of the AG’s Office. A special prosecutor was deemed necessary after at least one witness refused to meet with prosecutors just weeks before Marling was set to go to trial. Welch, however, could not provide an explanation for why he chose to use taxpayer funds totaling nearly $13,000 for this single case alone when the AG’s Office would have done it at no cost to the county, saying only that DeVillers and his team were ‘the best available resource for (this) particular case.’

While investigating, Y-City News uncovered that DeVillers was being paid out of the wrong fund, an account used and intended to be fully reimbursed by the State of Ohio for criminal defendants who can’t afford their own attorney when charged with a crime, what was later determined to be a ‘paperwork error.’

In another case where DeVillers was appointed by Welch, set for trial in mid-August, thousands of additional dollars were paid to the nationally-recognized law firm, again initially debited out the Indigent Defense Support Fund. Such errors have now been fixed and paid for not by the Prosecutor’s Budget but by the County’s General Fund.

DeViller’s investigation seems to have been centered on if administrators at Tri-Valley attempted to interfere with the Marling prosecution, but lacked a thorough in-depth look at if teachers, principals, administrators or board members failed to report suspected abuse allowing more young children to become victims. The difficulty in the case was that teachers, aids and staff members had reported early questionable conduct and suspected abuse to administers, who then failed to properly and legally report and intervene. Many of those with direct contact with district students expressed grave concerns about losing their jobs, licenses or careers if they made a larger issue about Marling’s conduct due to what they believed to be a favorable status Marling had with administrators.

In fact, less than a full work week’s worth of time was spent on the entire special investigation, where DeVillers and his assistant were given mountains of evidence that has taken Y-City News hundreds and hundreds of hours to review, leaving the question of if the same situation is bound to happen again after even top administrators were allowed to continue at their posts within the district.

Who was Cory Marling?

Cory Marling was born and raised in Muskingum County, having graduated from John Glenn High School and Muskingum University, he spent a few short years in Licking County at the public charter school Par Excellence Academy before applying for and being offered a position as a first-grade teacher at Nashport Elementary in the Tri-Valley Local School District, one of the best-funded in the region. From there, he would be promoted to assistant principal at Frazeysburg Elementary before becoming the school’s chief administrator the following year.

Investigators have found that even while still in college and student teaching at Adamsville Elementary, another school in the Tri-Valley district, concerns would be made about his conduct. When he accepted his first post-graduation assignment in Newark, concerns would follow. In fact, at every place he would advance to, concerns would be raised and in many cases escalate in severity.

After seeing reports being made to administrators and little, if nothing being done, a belief began to grow among teachers and staff that Marling was being protected, soon educators began becoming worried their own jobs and careers might be at stake if they continued to discuss or report concerns.

What had started as most likely just unwise physical touching escalated and eventually became grabbing girls’ butts, putting his hand up elementary-aged kids’ shirts and putting students on his lap, among other things.

Eventually, the level of misconduct became so brazen and frequent that the knowledge of what was going on began to spread through the greater community which led to an out-of-county report being made and child protective services receiving an anonymous phone call reporting the ‘disturbing activity’ at Frazeysburg Elementary.

It would take nearly two more weeks until Marling would be placed on paid administrative leave and formally separated from the building where his abuse was then occurring. Months later, he would be indicted by a Muskingum County Grand Jury on 11 counts of gross sexual imposition, realistically facing the rest of his natural life behind bars, which also legally forced the district to suspend him without pay. He amassed roughly $55,800 in the nine or so months he was on paid leave. Marling’s departure also required the district to bring in a long-term substitute principal, a need the district had until the 2020-2021 school year when Heather Campbell was moved from Dresden Elementary to Frazeysburg Elementary.

The prosecution of Marling would take multiple years, ending not in the anticipated two-week trial but in a plea deal in which Welch dropped felony charges for four misdemeanors without a sex offender reporting requirement.

Serving his first term as the county’s elected prosecutor, but not a stranger to the office, having served as an assistant prosecutor locally for many years, Welch called it of one the toughest decisions of his career. It ensured that Marling lost his various educator and administrative licenses, a request of his victims, severely limiting his access to children.

He would be sentenced to 340 days in the county jail and three years of probation, shocking the community and upsetting many. Some of Marling’s victims and their families spoke during sentencing, most mentioning their disappointment in administrators at Tri-Valley and their thankfulness to Welch during the entire ordeal for his support and guidance.

Why a Special Prosecutor

Welch deemed it necessary for a special prosecutor to be appointed because ‘as we progressed through the case and prepared for trial we became more concerned about potential conflicts with certain witnesses that we had subpoenaed to testify.’ That included the case of at least one witness who refused to meet with his office as the case progressed.

As Y-City News has previously exclusively identified, the district’s Superintendent Mark Neal had his cell phone taken in the Summer of 2019, an action we are told is almost unprecedented in school child sex abuse cases, for his failure to report abuse. Soon thereafter, efforts were made by Neal to shore up testimony and evidence that would paint school administrators, especially himself, as the chief administrator of the district, as having done everything he was legally required to do.

Throughout the years, multiple concerns were made to Neal about Marling and he was at least aware of questionable conduct. On at least one occasion he spoke directly to Marling about altering his physical interactions with children.

When Marling took over as the sole administrator at Frazeysburg Elementary in the Fall of 2018, his behavior escalated and teachers and staff, still extremely fearful for their jobs but wanting to protect the children, went to their union boss, hoping he could communicate to Neal and other administrators that something had to be done.

Welch said that during that meeting Neal was told that ‘you have teachers and parents at Frazeysburg who are concerned about your principal being too affectionate…’ as well as being provided specific details regarding Marling ‘straddling’ female students and holding at least one child on his lap.

In the days after his cell phone was taken, months into the detective’s investigation of Marling, Neal reached out to numerous staff members asking them to provide in writing what was told to him or not told to him about Marling, each of those witnesses in the Marling case.

One of those individuals was that union boss. In an email exchange obtained by Y-City News in a public records request, Neal appears to be pressuring that individual, who is also a teacher in the district, to alter his statement.

“I don’t believe there was any specific information such as (sitting on his lap or straddling students on the floor) that was shared when we met,” Neal wrote to the union boss. “Please edit and re-send your letter to reflect that if you believe it to be factual.”

On another occasion, while the investigation was again still ongoing and nearing prosecution, Neal called a meeting of the entire Frazeysburg staff and went over the law about mandatory reporters, including specifics about how staff members who didn’t make a report directly to Child Protective Services could face criminal charges, scaring many into not wanting to help any further in the investigation.

In another case, just weeks before the trial, someone in the district reported those teachers, who were going to be called as witnesses, to the Ohio Department of Education for failing to report abuse, which could have resulted in the staff members losing their licenses and thus their careers.

Welch maintained custody of the prosecution of Marling, but ultimately felt that a special prosecutor was needed at that point due to those complexities.

In Welch’s filings with the court, needed due to a judge being required to sign off on his request to appoint a special prosecutor, he simply wrote: ‘there exists a matter that has not yet been made public, in which the public interest would be best served by having said attorneys act as special assistant prosecuting attorneys on behalf of the State of Ohio.’

When asked to elaborate, Welch said that ‘a special prosecutor was requested by the Muskingum County Prosecutor’s Office due to potential conflicts that existed as a result of some necessary witnesses also being investigated for the crime of failure to report abuse.’

As for why he moved to have the entire order sealed, Welch said ‘the request for the sealing of documents had to do with concerns about pre-trial publicity impacting the ability to seat a jury in the event that the case proceeded to trial.’

The move was not unique, after Marling’s defense attorney sent a statement for publication to Y-City News, Judge Mark Fleegle issued a gag order on both the prosecution and defense to ensure the integrity of the case in the weeks before trial, a common tactic in high profile cases.

“There were concerns that because the case had received so much media attention that finding jurors who had not heard any details of this case and who had not informed an opinion on the case could create a situation where we would start the trial and end up running out of potential jurors,” Welch explained. “Obviously not something we wanted to put victims and witnesses through.”

Court documents show that DeVillers and his team were brought in a few weeks before the case was scheduled for trial.

The scope of the special prosecutors, according to DeVillers, was to see if there was any interference with the Marling investigation or prosecution by Superintendent Neal or anyone else that could result in criminal charges. DeVillers said they also looked to see if anyone failed to report abuse they observed or were told about.

Within hours of the publication of a story by Y-City News that those teachers had been reported to ODE, Welch told us that there was an ‘ongoing criminal investigation regarding conduct of an individual or individuals employed by Tri-Valley surrounding the Cory Marling case’ and that ‘the investigation does not involve any teachers.’ That statement was made on Wednesday, August 25, 2021, just 12 days after DeVillers and his associate, Michelle Nicholson, were appointed special prosecutors under the sealed court order, but after Marling had pleaded guilty to misdemeanor charges.

There remains strong evidence that teachers and staff were extremely concerned about losing their careers and thus their livelihoods if they had reported Marling to Child Protective Services during his tenure at Tri-Valley. The main failure appears to be that, among other things, administrators had created an environment, unlike in which exist at other neighboring districts, where concerns were not welcomed and would not be properly addressed, including that those same administrators themselves failed to report suspected abuse to Child Protective Services, except for them, they did not report being concerned for losing their careers if they had made the report, as they are also legally mandated reports.

So why DeVillers and Nicholson with Barnes & Thornburg?

This is the part of the investigation we had to put in some significant time to better understand what is and isn’t typically in the appointment of special prosecutors.

As there is no file at the courthouse where all cases that required a special prosecutor reside, we had to rely on our own internal documents, court filings and other available material to first locate when and then how special prosecutors had been previously appointed in Muskingum County.

It wasn’t a perfect method, as the digital public-facing system the county uses doesn’t differentiate when a special prosecutor is in charge of a case, wrongly displaying the elected prosecutor at the time as the one with ultimate authority over the prosecution. Making it more difficult, in cases where no charges were brought by a special prosecutor, there is little if any way to identify an investigation, nonetheless, we determined, at least in cases that lead to an indictment or charge by a special prosecutor, were extremely rare.

Each year hundreds of felony charges are filed in Muskingum County, and in most, records show no appearance of a special prosecutor.

The most recent criminal case in which a special prosecutor was appointed was in the death of Adrian Ramos in late 2020. Franklin County Assistant Prosecutor Daniel Cable was requested and assigned that case. Cable has assisted many counties around Ohio when they requested his experienced prosecutorial knowledge in acting as a special prosecutor.

In previous years, such as in the criminal case of Robert Riggs in 2019, Franklin County Assistant Prosecutor Doug Stead has also helped Muskingum County when the need arises.

Only in one case did we identify another time in which a private attorney was used as a special prosecutor in Muskingum County, in the investigation of the death of Grant Hickman, nearly a decade ago under former elected County Prosecutor Michael Haddox.

To identify if the appointment of a private attorney as a special prosecutor was normal or abnormal we reached out to numerous county prosecutor offices around Ohio.

In all but one of the thirty-plus offices that got back to us, they identified using only other counties or Ohio’s AGs Office when they needed a special prosecutor due to a conflict of interest, a situation where there might be a perceived conflict of interest or in the case of much smaller population counties, when they lack the expertise for a difficult and complex case.

Some counties, such as Delaware, use neighboring counties exclusively, chosen based on the skills and availability of prosecutors that can be lent. Others such as the counties of Perry and Morgan use the AG’s Office exclusively. Pickaway County, for example, uses a blended approach.

Athens County Prosecutor Keller Blackburn, who said he is very active in the Ohio Prosecuting Attorneys Association, provided insight into how counties offer their prosecutors to other counties at no expense, explaining that there is a system they and others use to tally trades to make sure it’s an even exchange to local taxpayers over time. All said the use of a special prosecutor was rare, most couldn’t cite a number of cases per year in which one was necessary.

None of the counties who got back to our inquiry said they charged for their services. The AG’s Office said if a case goes to trial they sometimes, if the need arises, charge the county for lodging, but that is the only expense a county would be expected to pay.

Franklin County First Assistant Prosecutor Janet Grubb said her office sometimes does employ a third option, retired highly experienced and trusted former senior prosecutors with decades of previous experience in their office in unique and special cases, such as in the high-profile prosecution of Jason Meade, whose victim’s family said they were going to sue the Franklin County Sheriff’s Department, a department the Franklin County Prosecutor’s Office legally represents as an agency of the county.

“I’m not surprised that some of the 82 smaller population counties do not try to use private counsel because at times it can be expensive and their budgets are probably a lot smaller than our budgets,” Grubb said in referencing why they were the only county, besides Muskingum County, to employ that third option of private council among those who got back to us.

Welch, for example, who makes around $140,000 a year, or roughly $67 an hour assuming a conservative 40 hours per work week, receives significantly less per hour than what DeVillers and Nicholson charged at roughly $367 an hour for their services. His assistant prosecutors make even less. That was also at a ‘deeply reduced’ discount to their standard rate, according to Welch.

DeVillers said he only does a few of these types of cases a year, adding that his appointment as a special prosecutor was the first criminal prosecutorial investigation he’s done for a county since at least retiring as a federal prosecutor in early 2021.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the median yearly per capita income for an employed Muskingum County resident is only $26,376 meaning that the investigation cost the rough equivalent of six months of work for an average citizen, an expense the county did not have to incur.

Welch challenges the Narrative

Welch, who we must acknowledge for being extremely timely to our many requests for further clarification and information, said that DeVillers and his team were the ‘best available resource’ due to the case being ‘complex, time intensive, sensitive in nature and a case of great significance within our community.’

“This combination of factors would have placed an extraordinary workload and timeline burden on another prosecutor’s office that I felt would be unfair to everyone involved in this matter,” Welch added. “This investigation needed to (be) handled promptly using the best resources available to the residents of Muskingum County and that resource was David DeVillers.”

Numerous individuals echoed Welch’s remarks that DeVillers has an ‘impeccable background and credentials’ as well as the high number of his ‘noteworthy, challenging and complex cases.’ Indeed he even was once an assistant prosecutor in Franklin County handling the prosecutions of organized crime and gangs in one of the state’s biggest counties, earning him much praise and recognition before leaving for federal service.

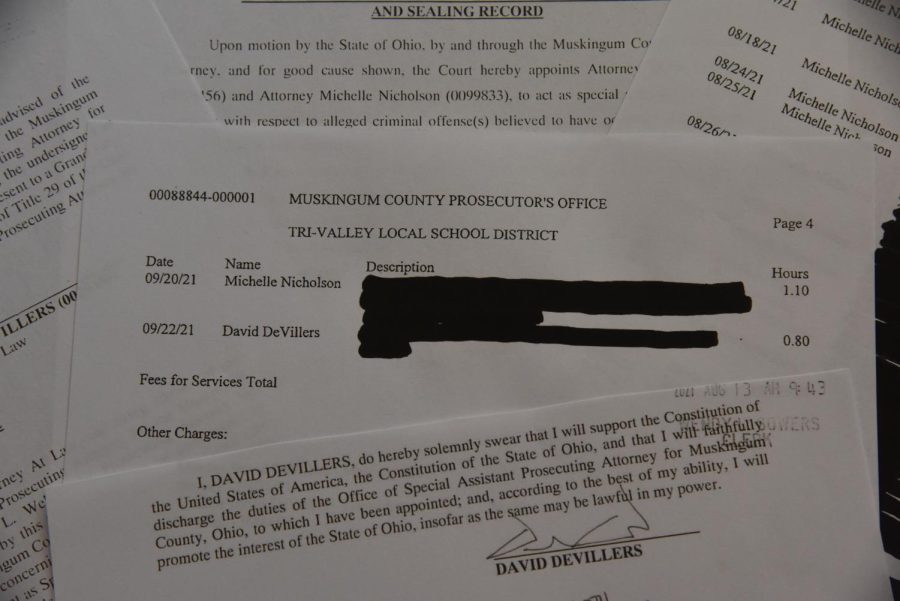

Welch puts forth the argument that another county wouldn’t have the time to handle the case, calculating our own time spent investigating, we assumed hundreds of hours were likely logged in the investigation, instead we found that in total the county was only invoiced for 33.4 hours of work from Barnes & Thornburg. In fact, his associate Nicholson, who has no prosecutorial experience, logged 25.5 hours in the investigation, roughly 75 percent of the work.

According to DeVillers, he conducted most of the interviews and his associate Nicholson did most of the document review and research.

“I don’t solicit, but I will entertain a request if one comes,” said Franklin County’s First Assistant Prosecutor Janet Grubb about lending her prosecutors out to other counties. “We have way too much business here to generally offer our prosecutors to other counties on a carte blanche basis, I mean we have to be selective as far as what we will respond to because the press of business here is incredible. I mean just for example a senior attorney like Dan Cable who’s been here for well over 25 years likely has between 10 and 15 homicide cases assigned to him.” Further, Grubb explained that her office has over 200 open homicide cases at a time when prosecutor offices around the country are struggling to retain and attract talent.

However, Welch would not elaborate beyond his previous statement on why he chose the firm over the AG’s Office which has an entire team of prosecutors available for this exact type of scenario, those with recent state-level crime prosecutions and knowledge of how to investigate school sex abuse cases, including the misdemeanor offense of failure to report.

Instead, Barnes & Thornburg invoiced the county for $12,445.44 for their services.

What did the Special Prosecutors Investigate/Find?

According to DeVillers, he found ‘unwise and reckless’ behaviors by administrators at Tri-Valley but nothing that he believed was intended to interfere with the Marling prosecution.

“I did find there were at least three problematic conversations that were had that could affect an investigation that were unwise perhaps even reckless, yet didn’t reach the level of intent to either hinder the investigation of Marling or the prosecution of Marling,” said DeVillers who added that he ‘didn’t do a deeper investigation’ into the failure to report abuse but that he didn’t ‘think it met the elements either.’

In fact, our own reporting and investigation into the matter seems to collaborate that finding, it wasn’t that school administrators such as Superintendent Mark Neal were working to derail the Marling Case, but were working to protect themselves from their own failure to report suspected and disclosed abuse to the proper authorities. Neal’s oldest son, who is the Law Director for the City of Wapakoneta in northwest Ohio, had been his go-to legal counsel, however, as the evidence mounted, he hired one of Columbus’s most expensive and renowned attorneys to represent him, Attorney Mark Collins. It’s unclear if the district paid that expense.

The Marling Scandal created a problem for Neal that has not yet been disclosed. After his phone was taken by detectives, along with for other reasons, Neal began applying for other school administrative positions around the state. Soon he found that districts had no interest in even entertaining someone for consideration that had done so little to protect vulnerable students, effectively trapping him at his present district in northern Muskingum County.

At one point, upset that his own inactions were being discovered by investigators and would likely become public knowledge as the Marling Prosecution advanced, he wrote an email to board members that he was considering departing the district.

“It just really is beginning to be too much,” Neal writes. “At this point, I am seriously contemplating filing a lawsuit against a few different county officials and offices and I do not want to bring that type of negative attention to Tri-Valley Schools.”

The misdemeanor of failure to report, not the initial scope, according to DeVillers, but necessary as the two were so intertwined, was also much less severe, in the eyes of the law, than the felony charge had DeVillers identified that individuals did interfere or hinder the Marling Prosecution.

The difficulty that DeVillers and his associate Nicholson faced was identifying what employees at Tri-Valley observed and if that should have been reported to Child Protective Services. According to DeVillers, they did make reports, but it was to supervisors or union representatives. It’s unlikely any individual teacher or staff member know the extent of Marling’s conduct but as information flowed up, it’s very pleasurable that someone, a principal or an administrator, knew the various pieces showed a more concerning story than just a young former teacher, at that point now-principal making unwise interactions with students.

During our investigation, we reached out to the Ohio Department of Education as well as to multiple other agencies to see what they considered the threshold for mandatory reporters or if the law had changed possibly since one of our previous articles.

It had not, current training material matches the Marling Case almost identically as a ‘failure to report’ not just for teachers but also for administrators. The reason, according to multiple interviews, that reports are mandated to be made outside the organization is so that politics and the career-track of administrators aren’t a factor, among many other things, in the safety of society’s most vulnerable members, its children.

Though without the testimony of the teachers and staff, it’s nearly certain that Marling may have walked free. The overarching concern becomes what happens in the next case as there is now a legal standard in Muskingum County that failure to report is satisfied when someone above them is told or that even administrators don’t have to report. As teachers and staff began altering their statements or not wishing to provide more information because they thought they might be legally prosecuted, many of them because they were told to ‘correct’ what they had said previously to make it ‘more factually accurate,’ for district administrators, under distress their jobs and careers could be at stake, they did what those administrators wanted most, not to interfere with the prosecution of Marling but to protect themselves and their careers, muddying the waters, which successfully halted any potential charges to the district’s upper echelon.

“I do think the conduct of Neal definitely was reckless, I mean he was jumping around an ongoing investigation and prosecution but I just don’t think he was doing it for the purpose of interfering with that investigation/prosecution (of Marling),” said DeVillers. “His concern over it did appear to be a concern over the failure to report, now I can’t say that he didn’t (fail to report) and I didn’t find that he did.”

No criminal charges were brought by DeVillers or Nicholson against any Tri-Valley district employees or board members. A final report was submitted by DeVillers to Prosecutor Ron Welch, however, it’s confidential to protect those who were investigated but not criminally charged.

Y-City News continues to investigate. Do you have additional information about the Marling Case, other information you think our news organizing should know about or want to bring our attention to a matter that needs investigating? We would like to hear from you. Contact us at (740) 562-6252, email us at contact@ycitynews.com or mail us at PO Box 686, Zanesville, Ohio 43701. All sources are kept strictly confidential.

lura parsons • Sep 2, 2022 at 3:37 pm

The decision whether Marling should go to PRISON For *A Long Time, should Be an *Easy One!! ♡Assaulted LITTLE One’s♡ have to live with that horrid TRAUMA for the rest of their lives! [TRUST Me!, ☹️, I KNOW!!]. Welch did something that was extremely hard for him to do!, he said so himself! BUT,, my Thoughts is, this very hard case should have been turned over to a ★”HIGHER COURT↑”★, because of it hitting so close to home with Local Court Officials. My Heart goes out to ALL the Families of the Precious ♡Lil One’s♡ who will have to some how, comfort them thru this!! PRAYERS!! PLZ!, Allow my Thoughts to Stay here!!! Thx!

Lori Myers • Aug 28, 2022 at 5:50 pm

Welch is just as guilty as Carling as far as I am concerned!

Carla Bunting • Aug 27, 2022 at 8:21 am

Thank you Y City News for keeping us updated for all the injustices for the children at that school district.

Carla • Aug 24, 2022 at 2:00 pm

Marling should serve his time like any other pedophile and be made to register as Sex Offender! Superintendent needs to be replaced ASAP ! Neither one of them have any respect for children, their safety or protection from deviants. Great job Y-City News, keep the updates coming.

Richard • Aug 11, 2022 at 4:28 am

Isn’t Welch related to Marling by marriage? Marlings wife’s maiden name is WELCH ! This may be why or part of why he used an independent law firm?