Officials meet in Zanesville to discuss redistricting of legislative districts

August 27, 2021

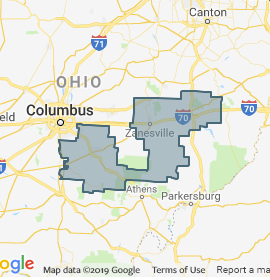

Ohio University Zanesville was one of only ten sites chosen throughout the entire state earlier this month for public hearings on redistricting of legislative districts.

State officials heard from dozens of Ohioans who discussed their concerns and hopes for what the commission will present, in the form of updated districts, later this year, as required by newly enacted state law.

Near the conclusion of each decade, as required by the U.S. Constitution, a census is taken of every living person within the borders of the United States.

Those figures are then used by the government to determine how many U.S. House of Representatives districts each state receives.

The most recent 2020 Census, for example, ultimately left the state losing one of its 16 seats, a trend that has been occurring since the 1960s.

In addition to federal congressional districts, data from the Census Bureau is used by numerous governmental bodies to equalize and redraw representative districts.

Not only will the State of Ohio use this data to redraw its legislative districts, but cities such as Zanesville will also do the same when it redraws the boundaries of its six wards.

In Ohio, the state’s Redistricting Commission is tasked with producing updated maps and districts for both the state Senate and state House of Representatives. U.S. Congressional districts are set by state legislators and only handled by the Commission if new boundaries can not be agreed upon.

The Commission is made up of seven members: one individual appointed by the state Senate President, one individual appointed by the state Speaker of the House, one individual appointed by the state Senate minority leader, one individual appointed by the state House minority leader, the Governor, the Auditor and the Secretary of State.

Maps drawn by the Commission are valid for 10 years if at least two Commissioners from each major political party vote for them. Should the maps be passed along strictly partisan lines, the maps are only valid for four years.

One of the major changes now required by state law is that there is a requirement that districts are compact. The legal language of the amendment also strongly discourages the splitting of counties, cities, villages and townships.

Ideally, the new law, passed by Ohioans in November 2015, will result in districts being less sprawled.

According to University of Cincinnati Political Science Professor David Niven, Ohio is the second most gerrymandered state in the country.

Gerrymandering is the practice in which legislative districts are unfairly drawn to advantage a particular political party or group.

In Ohio, Republicans, the current political party in charge, have significantly more state House and Senate legislative seats than the aggregate number of Ohioans who vote Republican. In previous decades, Democrats were known to use the same tactics now employed by Republicans to advantage themselves unfairly with legislative seats.

During Wednesday’s meeting at OUZ, dozens upon dozens of citizens spoke about the redistricting process and what they would like to see be implemented by the Commission.

Jen Miller, Executive Director of the League of Women Voters, whose organization participated in both the 2015 and 2018 ballot initiatives in which gerrymandering was outlawed within the state, said the process of creating political districts to unfairly advantage the ruling political party has been occurring since the formation of the republic.

“Today using sophisticated data and software parties can rig a legislative district for a particular party or candidate to absolute precision,” Miller explained, citing the use of supercomputers and invasive data collection to link information about individuals to voting predictions.

One of the concerns Miller said she often hears from both Republicans and Democrats is that due to these unfair districts, in which whoever wins the primarily nearly always wins the general election, representatives are less accountable to their constituents, knowing they will likely get re-elected with ease.

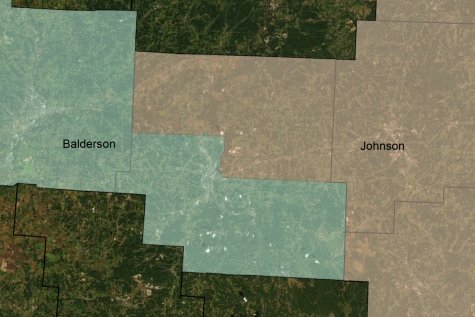

Diane Jahnes, who attended Wednesday’s meeting and lives in Hopewell, said that her U.S. Congressional District, currently the 12th district represented by Zanesville native Troy Balderson, stretches from Muskingum County clear up into Delaware County.

As reported by Y-City News back in 2018, the issue of the county being split between congressional districts also caused confusion for many local voters when Balderson ran for the special election to Congress in August against Danny O’Connor, Franklin County’s Auditor. Balderson’s district only covers roughly half of Muskingum County. The northern portion of the County is covered by Congressperson Bill Johnson, who represents the state’s 6th district.

Jahnes added that she thinks her district looks like a salamander. Noting how she, a rural Muskingum County resident, shares little with her Columbus counterparts.

While it’s currently unknown if the Commission will ultimately have to also resolve the state’s federal congressional districts, those boundaries will no longer be allowed to be as sprawling as to stretch from Muskingum County west around Columbus and north to wealthy Delaware County.

Ohio State Auditor Keith Faber (R), who attended Wednesday’s meeting instead of sending representatives in his place, alleged that many of those coming to speak at OUZ were ‘paid operatives’ spewing ‘activist talking points.’

Faber said he found most helpful comments by those individuals who provided specific examples and issues on how the Commission will have impacts on their lives. Citing an individual from Licking County, Faber explained how in her testimony, she said living in the eastern portion of her county, she more aligns herself with Muskingum County voters than those in Newark.

The Auditor did mention that he wants to see 10-years maps come from the Commission, instead of the four-year maps should both parties not agree, calling it his priority and necessary to have bipartisan buy-in for a successful redistricting.

Meanwhile, Ohio State Senator Vernon Sykes (D) from Akron, said he was pleased to hear ‘passionate and informative testimony.’

“It’s always a challenge,” said Sykes. “Political decisions are extremely important. There is a war between the two parties and when you have warfare there will be some casualties.”

Those casualties, as Sykes refers, are the unlucky House and Senate members who will be forced to run against colleagues when their districts are reshuffled. Some have already said they plan to retire if such changes affect their districts.

When Zanesville’s wards were most recently redrawn, one of the requirements was that each of the six ward representatives not be out-seated, meaning the current ward they represented no longer included their place of residence. Due to more strict and stringent requirements at the state level, that is unlikely to be entirely possible with the state House and Senate districts.

Another local speaker at Wednesday’s event was Steve Kullman, a nearly 40-year resident of Muskingum County and union member of the American Federation of State – County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) Local 11 AFL-CIO.

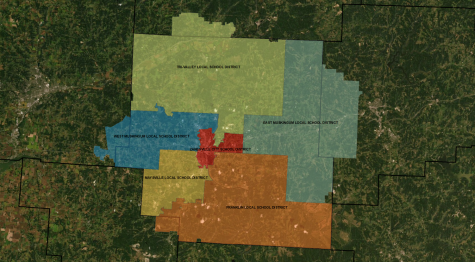

One of Kullman’s concerns was that at the local level, many school districts and communities are split between various state legislative and congressional districts.

Kullman highlights one of the major issues rarely discussed as part of the redistricting process. While state law now all but prohibits splitting townships and villages, and for the most part cities, except for the rarest of instances, school districts in Ohio are an entirely different situation.

Unlike many states who during the 1950s and 1960s merged all school districts within a county into one school district, Ohio did not, resulting in the state having far more school districts per capita than its peers.

That often unorganized merger process resulted in local-centric approaches that don’t conform to other legal boundary lines.

Tri-Valley, for example, has students within its district that live north over the Muskingum County line into Coshocton County. East Muskingum has multiple townships in Guernsey County that have been students at their schools for over half-a-century. Franklin has some students who live in Perry County and there are still yet those students who live in Licking County and attend West Muskingum.

In his speech, Hullman spoke about the need for more ‘fair’ districts and his concern that the more gerrymandered a district was the more likely the elected official would feel they needed to only appeal to their narrow base and ignore the rest of their constituents.

Susan Haas, an eastern Licking County resident, also spoke Wednesday, revealing she had helped in 2017 to collect signatures for the ballot initiative, providing insights to the wide range of voters she spoke to when going door-to-door.

“People from all walks of life signed my petitions,” Haas said. “People who identified themselves as Republicans, Democrats, Independents and at least one Libertarian. Young, middle-aged and old; Black, White and Asian. People in business suits, biker leathers, tie-dye and work clothes. People whose hands, as they signed, showed manicured nails and expensive jewelry; people whose hands were rough and calloused from years of manual labor.

As Haas explained, of the nearly 600 people she collected signatures from, they only had one thing in common, besides being registered voters, they all wanted an end to gerrymandering.

In both the 2015 and 2018 ballot initiatives, the three counties Haas collected signatures from, Licking, Muskingum and Perry, all three voted in favor of the anti-gerrymandering amendments by a margin of two to one.

Haas cited an example in Licking County for the 71st Ohio House race last year and how it favored the Republicans to such a degree that whoever won the primary would win the general.

Featuring two self-proclaimed moderate Republicans, Haas explained how the Republican primary was an expensive and bitter race between the two which pushed both candidates to espouse the most extreme positions to capture the lower turnout of passionate voters who are known to participate in primary elections.

In closing, Haas also cited the other Ohio House district currently represented in Licking County, the 72nd district, where she resides.

“Where I live, had been represented by an individual with an absolute lock on the district,” said Haas. “It was common knowledge that there was no point to challenging him in a general election, unless something bizarre happened, like his getting arrested. So when he actually did get arrested, there was no other candidate named on the ballot.” That representative was Larry Householder, ex-Ohio House Speaker charged in the $60 million dollar bribery scandal.

“A healthy democracy depends on primary elections where candidates appeal to the broadest range of their party’s supporters,” said Haas as she collected her pages of notes. “General Elections that are a forum for ideas that could benefit all the district’s residents. Districts where people with common interests share a common representative with what we voted for in 2015 and 2018, and that’s what we demand now.”

Also in attendance and speaking Wednesday were many residents from the Columbus region as the state did not have any of its ten public hearing sessions in Franklin County.

New maps are expected later this year by the Commission.