Ohio boasts advanced traffic management center, lives saved while alleviating congestion, deployment of new tech

A Cleveland assigned operator handles a slowdown on I-90 at East 185th Street near Euclid Hospital and Villa Angela-St. Joseph High School along the lakefront.

July 12, 2022

At a secure location west of downtown Columbus exists what is arguably one of the country’s most advanced and cutting-edge traffic management centers.

There, operators, who sit behind a row of computer screens, alleviate congestion and route traffic around critical incidents like fatal crashes and road-closing snow storms, making the state’s roadways safer for all motorists while deploying and refining technologies that are being replicated around the globe, once again showcasing the excellence Ohio has in an ever-changing technological landscape.

As companies like Intel chose to make Ohio home for its new state-of-the-art chip foundries, leaders from the private sector and government are coming together to curate ideas and technologies that will be integrated into the services of tomorrow. Solidifying the once manufacturing hub of the country into a knowledge-based economy that should uplift and advance the quality of life for all Ohioans.

Scroll back the clock a few decades and traveling by vehicle was far different than we care to often acknowledge. There were no in-car GPS units, smartphones and things like Google Maps were only but a theoretical concept, and no one was sitting behind screens watching hundreds of cameras and the reports from nearly as many sensors to predict and respond to irregular traffic flows. Sure, officials knew that Thanksgiving was one of the most traveled holidays, as it remains today, and an advancing weather pattern likely meant white snow on top of black asphalt, but there was little state-wide coordination across Ohio to do anything about it, at least in realtime.

The greater Cincinnati metropolitan region was the first in the larger multi-state area to attempt anything on a large scale at organizing, analyzing and responding to ever-changing traffic flows, that endeavor began during the late 90s. ARTEMIS, a traffic camera monitoring system, covered the state’s third most populated city, along the Ohio River, and a decent chunk of northern Kentucky. By today’s standards, it was a modest, roughly patched-together approach, but to those pioneers, it was something that hadn’t been done in the state, let alone the city before.

Over time, some of Ohio’s other highly populous cities did the same. That may have been a few cameras at points of large roadway mergers – that always seemed to cause slowdowns at best or a road-closing fatality crash at worst – or it could be calculating and displaying route times alongside roadways to give drivers information. That was in addition to radio traffic reports that were all the rage in their day, some by profit-seeking stations and others by far too often monotoned, cryptic-sounding government employees, broadcasting information over the airwaves.

For Ohio, it was the Department of Transportation that would pick up those regional centers and pull them all into one centralized location. It wasn’t always as advanced and as cutting-edge as it is today, ODOT was once colocated at the City of Columbus’s Traffic Management Center.

Around the conclusion of the first decade of the 21st century, the state agency branched out from that joint site in the center of the state and constructed its own, this time with the ultimate goal of managing Ohio’s roadways in one central location.

What exists today is a much larger version of what was around pre-2019, a few desks in a cramped room. Change would flash to the horizon when in 2015, just days before July 4th and Red, White & BOOM! in Columbus a tanker truck carrying roughly 10,000 gallons of ethanol overturned and exploded, damaging a critical roadway overpass carrying I-70 eastbound traffic. Worse, the route the tanker was traveling on underneath that bridge was I-270, effectively crippling a large artery and interchange on the city’s west side.

ODOT’s executive team sprung into action, arriving at the small and less-than-roomy Traffic Management Center only to find it nearly impossible to collaborate while operators continued their vital work, directing traffic around the closure, and managing Ohio’s other many major roadways.

ODOT’s Statewide Press Secretary Matt Bruning was there, part of the executive team, who had to figure out how to respond, protect lives and keep commerce flowing.

“We were all huddled into this little teeny-tiny TMC trying to manage the situation while these guys were trying their best to manage the traffic situation,” Bruning recalled.

At record pace, the route was diverted and quickly fixed, a task that made national and international news, while the effort showed just how good the state was at handling and responding to emergencies, one thing was clear, they needed more space.

As mentioned previously, that work led around 2019 to a much larger and more capable operations center. If it wasn’t already, those upgrades, both at the center and around the state – with the implementation of high-definition cameras and advanced sensors – brought the state to the forefront of what was and is possible, not just here in the Continental United States, but around the globe.

“We’re the best at what we do in the nation, it’s not even close,” proudly explained Dominic DelCol, the TMC’s second shift supervisor.

In fact, representatives from nearly twenty other states recently visited, met with operators, and learned about technologies and practices that they intend to take back to their respective states, cities and agencies for implementation.

From traffic cameras and roadside weather stations to digital variable speed limit signs and advanced SmartLane corridors, by being a leader in road tech, the DeWine-Husted Administration has previously said they hope it will encourage high-tech private investment in the state, the likes of which would be electric vehicle manufacturers, regional offices of major tech giants, and the location of semiconductor fabs where raw silicon wafers are turned into integrated circuits, such as what Intel plans to do with its advanced chip producing site in New Albany.

What an Operator Sees

In a large, sprawled-out room, the likes of which resemble a 911 call center or a real time crime center, 12 desks, each with as many as eight to ten screens, light up before an operator as they manage a greater metropolitan area.

Typically, during the first and second shifts, when commuters are headed into towns and then when they leave for home, respectively, anywhere from four to six of the stations are occupied.

With room for growth and or response to an emergency, and the need to light up additional stations for more operators or response coordinators, the floor is often only lightly filled, regardless, stations are modestly separated to give staff enough space to have their own bubbles but not too far apart to prohibit working in pairs or as a full team if the need arises.

Jon Upchurch is one of those operators and a Traffic Management Center Specialist, a position between a layman operator and a supervisor, often given unique tasks alongside his usual work such as testing, watching and analyzing new tech that the state hopes to expand across the state.

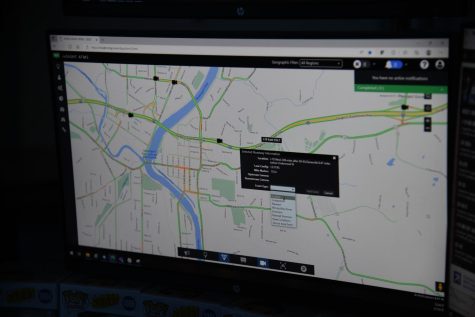

On the day of our interview, Upchurch had eight screens affixed along two rows as well as a large screen monitor to his left, for our demonstration, it displayed traffic cameras around the greater Muskingum County area.

In a typical layout, an operator will have a touch-capable screen with access to the state’s MARCS Radio System which provides a link to police and fire dispatch centers, ODOT work crews and even, if need be, individual officers, such as Ohio State Highway Patrol troopers. For Upchurch, that console is on the furthest left monitor on the bottom row. To the left, he has his ODOT email, which includes automated pertinent reports, as will be explained further down in this article. On the third screen from the bottle left, Upchurch has a portal in which he can input crashes, slowdowns or construction into what end-users know as OHGO, both a website and mobile phone application. A live view of that site can be seen on his right-most bottom screen.

On the top row, he has access to the City of Columbus’s camera traffic network, which supplements ODOT’s network. During our demonstration that was on the furthest left screen. The two screens in the middle display any two traffic cameras he so desires, both in full-screen mode or in a near limitless customizable format that can theoretically show up to 25 cameras each. On the top right, Upchurch can see the various traffic camera on ODOT’s I-670 SmartLane in Columbus, a special task that’s been assigned to him as the state works to expand the SmartLane project such as is currently underway with a $20 million dollar I-275 SmartLane in Hamilton County. Ohio’s SmartLane will be explained further on in this article.

For demonstration purposes, in a test-bed environment that wouldn’t affect the live system, Upchurch showed us just how quickly he can navigate between cameras, identify a slowdown or crash and input that information into OHGO which then populates that report via an API to applications such as Waze, Google Maps or Apple Maps, as well as many others. Within a few minutes, a motorist traveling west along I-70 in Muskingum County would get that notification that the interstate is closed up ahead and the choice to either stay on that particular roadway or take an alternative route such as US-40 to avoid the crash and resulting closure. From a driver’s perspective, the detour seems effortless, but behind the scenes was an operator diligently using sensors, cameras and data feeds from private sources to quickly locate issues and resolve them. Typically, that includes letting the regional dispatch center of the Ohio State Highway Patrol know so they can send troopers. Usually, in serious crashes, involving injuries and or fatalities, another motorist behind the collision dials 911 moments after it happens, sending first responders to the scene.

One point that Upchurch and Bruning wanted to make clear also was that unlike the public traffic camera viewer, which provides one still frame image every few seconds, a decision made by IT to save bandwidth costs and server loads, is not the experience at the TMC. Operators have access to live camera feeds, many newer cameras at 30 frames per second, which gives them a more detailed view of Ohio’s roadways. They are also able to pan, tilt and zoom the cameras around, something for obvious reasons members of the public can’t do via OHGO. When not actively used by an operator for that function, the traffic cameras have predetermined perspectives they rotate between for roadway coverage.

The state is usually split up into regions and an operator assigned to each. Northeast Ohio covers Cleveland, Akron and Youngstown as well as surrounding areas. Central Ohio covers Columbus, including cities like Zanesville, Southwest Ohio covers Cincinnati and Dayton and Northwest Ohio covers Toledo and its surrounding areas, typically that is. During the 3rd shift, the number of operators shrinks to two, but the amount of traffic and therefore crashes on the roadways do as well.

“You always got somebody who’s watching the cameras throughout the state,” said Bruning. “Even on Christmas morning, there is somebody here, 24/7/365. So if you are law enforcement and you need to reach ODOT, and you call the Traffic Management Center, someone will answer that phone around the clock.”

Of course, operators get busiest during morning and evening commutes. Certain holidays, like Thanksgiving, the Fourth of July and Memorial Day Weekend see noticeable increases in traffic, and according to Bruning, unfortunately, increases in crashes.

In addition to the 12 stations, there are also four large screens affixed to the front of the room along with multiple whiteboards. During the day of our demonstration, one displayed various Columbus traffic cameras, one major bridges around the state, one data from weather monitoring stations and one from various traffic cameras in Cincinnati. They like many of the screens in that room can be changed at a moment’s notice to handle the situation at hand.

Cameras

A core function of the Traffic Management Center is to collect feeds from cameras around the state. In urbanized areas, cameras are connected by fiber, in more rural areas cameras are often linked via an AT&T cellular modem.

Regardless of their route of transit, the various traffic camera feeds one way or another make it to the TMC. Some cameras like those covering the Veterans’ Glass City Skyway Bridge in Toledo and Cincinnati’s I-74 corridor are from the earliest generation, others are more modern, like the ones recently placed in Zanesville to help operators monitor the $88 million dollar interstate reconstruction project through town. A casual observer would be able to click on various cameras on OHGO and notice varying levels of quality from the images from each respective generation.

According to Bruning, it is a balanced effort to replace aging cameras while also deploying new ones throughout the state. In 2015, there were only roughly 500 cameras, today that figure has doubled, with more than 1,000 cameras actively watching Ohio’s roadways.

Even more camera feeds run into the TMC thanks to cities such as Columbus sharing access, which gives operators more viewpoints and ways to monitor traffic patterns in highly trafficked areas. Gahanna, located in Franklin County, will soon also have its street cameras accessible by operators. Upchurch added that while those feeds are accessible, only ODOT cameras are actively recorded and stored for 72 hours, should an operator need to rewind and check something out.

Some camera domes affixed along major roadways actually have four individual cameras or lenses, depending on the model, that gives a four-way perspective.

Even more advanced cameras, the ones ODOT hopes will soon become the standard deployed camera, have the capabilities to do so much more. Upchurch says he has been tasked with testing it and its life-saving features.

Near downtown Cincinnati located along I-71 at Reading Road is a camera capable of detecting wrong-way drivers. ODOT already has some wrong-way detection systems, but should this test be successful, it will mean that in the future, one day it may be possible to monitor and intercept a wrong-way driver anywhere a camera is watching. The camera works by creating three boundary lines, watching a one-way street, objects such as vehicles should only be traveling one particular way. If an object crosses all three lines in the opposite way, an alert is sent.

Upchurch gets an email within seconds, an attachment provides a roughly 12-second clip that he can review. Occasionally a person or the shadow of a bird may trip the system, which has its intensity settings set higher to hopefully catch every wrong-way driver while the camera’s capabilities are being tested.

During our demonstration, Upchurch showed us a video of a car that a day prior had gone the wrong way, triggering an alert, but the driver caught their mistake and quickly turned around, in that instance no further action was needed. Many areas that experience a high occurrence of wrong-way drivers, like this site, also have flashing lights that activate when a wrong-way vehicle is detected along with other visible and audible warnings.

Other times, Upchurch opens the email, usually within 30 seconds of the wrong-way vehicle being detected, sees a vehicle, whose driver is often under the influence of drugs or alcohol, go straight through the wrong way and he springs into action. Upchurch presses a button on his MARCS console that patches his voice into every police and fire dispatch center in Hamilton and Clermont Counties.

“We have a wrong-way driver who just entered from Martin Luther King Drive heading northbound in the southbound lanes, it’s a dark-colored minivan, be on the lookout for it,” Upchurch said during the demonstration of how he would normally respond.

Because of the type of injuries a head-on collision often causes, especially at higher speeds, that message is relayed to officers, who rush to intercept the vehicle.

A wrong-way driver last summer is an example of that and when operators pair up, Upchurch explained recalling what happened. Another operator and he began working together, tracking the wrong-way driver, and providing an update to the closest responding units. An officer, who was on a routine traffic stop, was able to rush to his vehicle, and off he was. According to Bruning, that quick action prevented the crash from resulting in any fatalities and protected the safety of other law-abiding motorists.

“We currently have a very high threshold for the alert for that reason,” Bruning said noting that eventually the system should be able to differentiate between a car and a human or bird’s shadow. “We’d rather it be too sensitive and save lives than not sensitive enough.”

Variable Speed Limit Signs

Unlike traditional street signs, digital variable speed limit signs offer the ability for operators at the TMC to adjust route speeds to conform to constantly changing weather and roadway conditions, especially during the winter months.

The TMC regularly receives updates about current weather patterns both from the National Weather Service and weather stations run by ODOT across the state.

In each of Ohio’s 88 counties, ODOT’s 175 combined weather and pavement stations provide vital data to operators. Weather stations give current air temperature, precipitation rate and type, surface temperature, subsurface temperature, dew point, relative humidity, and wind direction and speed. Pavement sensors provide data such as roadway surface temperature, traffic speeds and vehicle counts along Ohio’s interstates, U.S. routes and state routes.

There is a weather station located, for example, at the Muskingum County-Guernsey County line south of the Village of New Concord. There is a pavement sensor along I-70, west of Zanesville, by the AEP office building and transmission site.

Bruning explained that often times that information is used by various officials to prepare for and combat winter storms that bring snow and ice that often impacts driving conditions.

Cleveland often experiences the lake effect snow band, which can produce massive squalls: sudden, sharp increases in wind speed lasting minutes, as opposed to wind gust, which lasts for only seconds.

The variable speed limit signs allow the TMC to lower the typical speed limit of 70 miles per hour down to 60 miles per hour in the anticipation of a winter storm along a 12-mile stretch of I-90. Currently there are 18 variable speed limit signs.

As conditions worsen, the speed limit can continue to be lowered, all the way down to 30 miles per hour, if needed.

Upchurch explained that by adjusting the speed limit, when roadway conditions have deteriorated or when visibility lessens, they can safely get drivers to slow down, which have proven to significantly decrease the number of crashes.

Since its implementation, no fatal crashes have been reported due to weather conditions on that 12-mile stretch and crashes were reduced by 42 percent, according to ODOT.

Should weather completely close a roadway, operators can have speeds leading up to the closed portion of the road go from 60 mph to 50 mph to 40 mph to 30 mph, slowing down vehicles so they aren’t finding themselves slamming on the breaks. They also can use digital signs to alert motorists that a closure is up ahead, that is covered below.

“We slow drivers down so that when they hit that white-out they aren’t going 60 or 70 miles per hour,” said Bruning. “They are going at a speed at which they are better equipped to handle those conditions.” Upchurch was the pilot operator on that program as well.

Digital Signs

ODOT currently has over 250 digital signs. Those include message boards, travel time boards and slow traffic advisory boards. Like the traffic cameras and variable speed limit signs, the digital signs are updated and controlled by the TMC.

Currently, there are only five slow traffic advisory boards, three in Columbus and two in Cincinnati. Typically, according to Bruning, those signs are placed at points where traffic historically has congestion.

There are 19 travel time boards, most are along I-70 from Wheeling, West Virginia to Richmond, Indiana. There is one, for example, around Buckeye Lake in Licking County and five in Cambridge around the interchange of I-70 and I-77.

A unique feature of the new time travel boards is that they can display in multiple colors. Three frequent colors are green, yellow and red. Green means traffic is functioning normally, yellow, a slowdown, and red, a closure is up ahead.

“So it helps the driver understand, especially if you’re coming from Indianapolis to Pittsburgh, you probably don’t know that it normally would take you 11 minutes to get to say for example I-670,” said DelCol. “For the average driver, they can easily deduct that green must mean everything is running just fine. If they see red, they can easily think delay or closure up ahead.”

The signs also offer the ability to put custom text on the boards, such as ‘Crash Ahead’ or ‘Left Lane Closed Up Ahead.’ That means that they essentially can function just like the nearly 100 message boards around the state.

As mentioned above with the TMC feeding data to entities like Google and Apple for smartphone mapping applications, many cell phones and vehicles also collect data about their speed, send it to the company, which anonymized the data, then provides it to traffic management centers around the country. That is how, in part, the TMC knows about slowdowns in areas without cameras. This is how Google Maps also, for example, is able to show a red line on its mapping application where traffic is slower than what is typically observed.

I-670 SmartLane

The state’s first SmartLane was a nine-mile stretch of I-670 between downtown Columbus and the John Glenn International Airport. After the success of that, Ohio is now constructing another in Cincinnati along I-275 between U.S. 42 in Hamilton County and State Route 28 in Clermont County, its estimated completion date is Spring 2023.

“Ohio invented the SmartLane and now everyone else wants one,” said DelCol. “Vegas is putting one in, Wisconsin is as well. We are the only one to have signs in the full color band.”

A SmartLane is an additional travel lane that is only open during certain times to relieve heavy periods of congestion or to help with incident management, according to the ODOT definition.

Instead of adding an additional fully functional lane, which Bruning said would have cost upward of $80 million dollars, the state expanded the already existing shoulder.

For a $12 million dollar investment, which was mostly the cost of digital message boards and cameras, the nine-mile stretch in Columbus gives operators and the public what Bruning said is a ‘glimpse into the future.’

Utilizing over-the-road digital signs, operators can adjust digitally projected speed signs on the boards to accommodate changing traffic patterns and showdowns. Green arrows and red exes let drivers know if a lane is open or closed up ahead.

The emergency shoulder ‘SmartLane’ stays mostly closed, typically used for broken down or emergency vehicles, but during certain commuter-heavy afternoon hours, traffic slows and an operator, usually Upchurch, will open the additional lane for use.

Since the lane is primarily, for most of the day, just an expanded shoulder, ODOT’s Freeway Safety Patrol will check the lane for debris or vehicles before opening it. Cameras at the operator’s disposal also assist.

Should a crash occur in another lane, the digital signs give Upchurch the ability to change the green arrow to a yellow x a few signs back, giving drivers plenty of time to get over. Right before the closure, the sign would display a red x, indicating a shutdown immediately ahead.

The SmartLane also helps protect against the problems of unwittingly creating inducted demand in which by adding a full extra lane, motorists adjust their traveling behaviors, essentially refilling the roadway to its previous levels of congestion. This way, the extra lane is only used when traffic is at its worst and needed most, during peak commuting hours or when there is a closure in another lane.

Drones

While Bruning didn’t want to disclose too much pending a media announcement in the coming weeks, he did say the state has been investing in the use of unmanned aerial platforms to assist their crews in their daily tasks and planning for their use in the event of an emergency.

One type of drone, which is tethered to the ground, is capable of staying up nearly indefinitely, providing a unique additional view, this one from the sky. That feed can then be streamed back to the TMC, which, according to Bruning, can be quite helpful if a serious crash or emergency occurs in a part of that state lacking traffic cameras, allowing operators to still effectively handle the situation and reroute traffic.

“Eventually where it will go is that you’d be able to call the UAS Center and say ‘hey we have a crash at this location and we don’t have a camera out there’ and they’d be able to go to that location and launch a drone or fly it to that location and give us a realtime view of what’s going on,” said Bruning. “We could share that feed with the first responders, patching them into what’s happening so they could also see and respond accordingly in real time.”

The investment is making ODOT a leader, through their experimentations, in figuring out how departments of transportions around the country will use drones in their workflows and services of tomorrow. That includes using deconfliction radars to allow them to fly alongside police and medical helicopters during emergencies and how thermal cameras will let those on the ground spot warning signs they might not have been able to with their own eyes.

Ultimately, as technology gets cheaper, self-driving vehicles more prevalent and the TMC more capable, Ohio, which has the fourth-largest freeway system in the nation, doesn’t appear to be losing its lead anytime soon, constantly setting forth forward into uncharted territory as an example to other states of how best to forge ahead into what will no doubtably be an ever exponentially evolving technological decade.